At a Glance

At a Glance

🎯 Learning Outcomes

- Remember: Define geography as the "bridging discipline" between physical and human systems.

- Analyze: Distinguish between physical (landforms, climate) and human (culture, economy) geography.

- Apply: Apply key concepts of location, place, and region to analyze real-world scenarios.

- Analyze: Examine the forces of globalization and how local cultures adapt (glocalization).

- Analyze: Compare formal, functional, and perceptual regional frameworks.

🔑 Key Terms

Spatial Thinking, Cultural Landscape, Globalization, Glocalization, Demographic Transition, Map Projection, GIS, Remote Sensing.

🛑 Stop & Check

Reveal Answer

⚡ Common Misconception

Myth: Geography is just memorizing capitals and flags.

Fact: Geography is the study of spatial relationships—understanding why things are where they are and how they interact to shape our world.

📊 Regional Snapshot: The World at a Glance

Studying World Regional Geography requires balancing the vast scale of the entire planet with the specific, lived experiences of people in individual locales. Geography is the "bridging discipline" that connects our physical environment with human culture, economy, and politics.

ðŸ—ºï¸ Interactive Map: Global Regions

Geographers use regions to organize and simplify the complexity of the world. This textbook is structured around ten major world regions, each defined by shared physical or cultural characteristics. Explore them below:

Toggle the layers in the top-right to compare political boundaries with physical terrain. Notice how physical features like the Himalayas or the Sahara Desert often define regional edges.

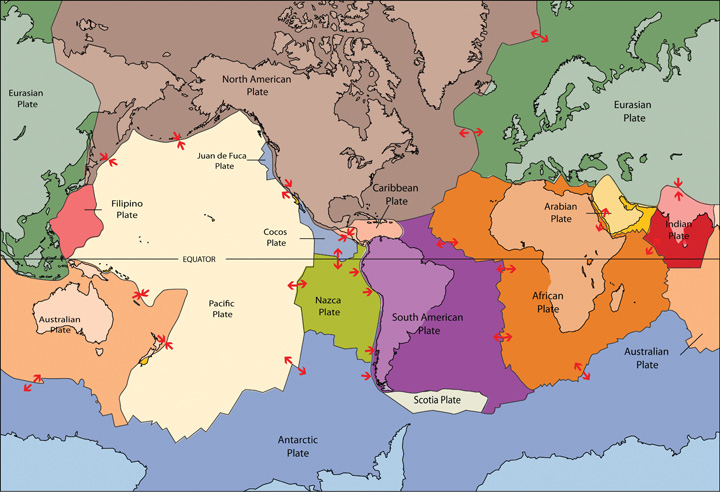

â›°ï¸ Physical Geography: The Natural Environment

Physical geography focuses on the natural processes of the Earth. It examines the "stage" upon which human history unfolds. By understanding these systems, we can better predict how environments might change and how humans must adapt. The discipline can be broken down into several key areas:

- Geomorphology ”“ the study of the Earth's surface features and landforms

- Climatology ”“ the study of climates and long-term weather patterns

- Biogeography ”“ the study of the geographic distribution of species

- Glaciology ”“ the study of glaciers and ice sheets

- Coastal Geography ”“ the study of shorelines and coastal processes

Climate Types and Human Settlement

Climate plays a fundamental role in determining where humans live. Geographers use the Köppen-Geiger Classification System to categorize the world's climates into six main types:

🌐¡ï¸ Climate Classification System

- Type A (Tropical): Warm year-round with high precipitation. Found near the equator in regions like the Amazon Basin, Central Africa, and Southeast Asia.

- Type B (Dry/Arid): Low precipitation with extreme temperatures. Includes the Sahara, Arabian Desert, and American Southwest.

- Type C (Temperate): Moderate temperatures with distinct seasons. Home to the largest human populations—found in Western Europe, Eastern China, and Southeastern United States.

- Type D (Continental): Cold winters and warm summers. Found in interior regions like the American Midwest, Central Canada, and much of Russia.

- Type E (Polar): Extremely cold with minimal vegetation. Located near the Arctic and Antarctic.

- Type H (Highland): Varies with elevation—mountain ranges can contain multiple climate types from base to summit.

Type C climates, though not the most widespread, have attracted the largest human populations throughout history. The abundance of forests, farmland, and fresh water in these moderate climate zones makes them ideal for human habitation. With over eight billion people on the planet, humans have filled most Type C regions and are now expanding into areas with other climate types.

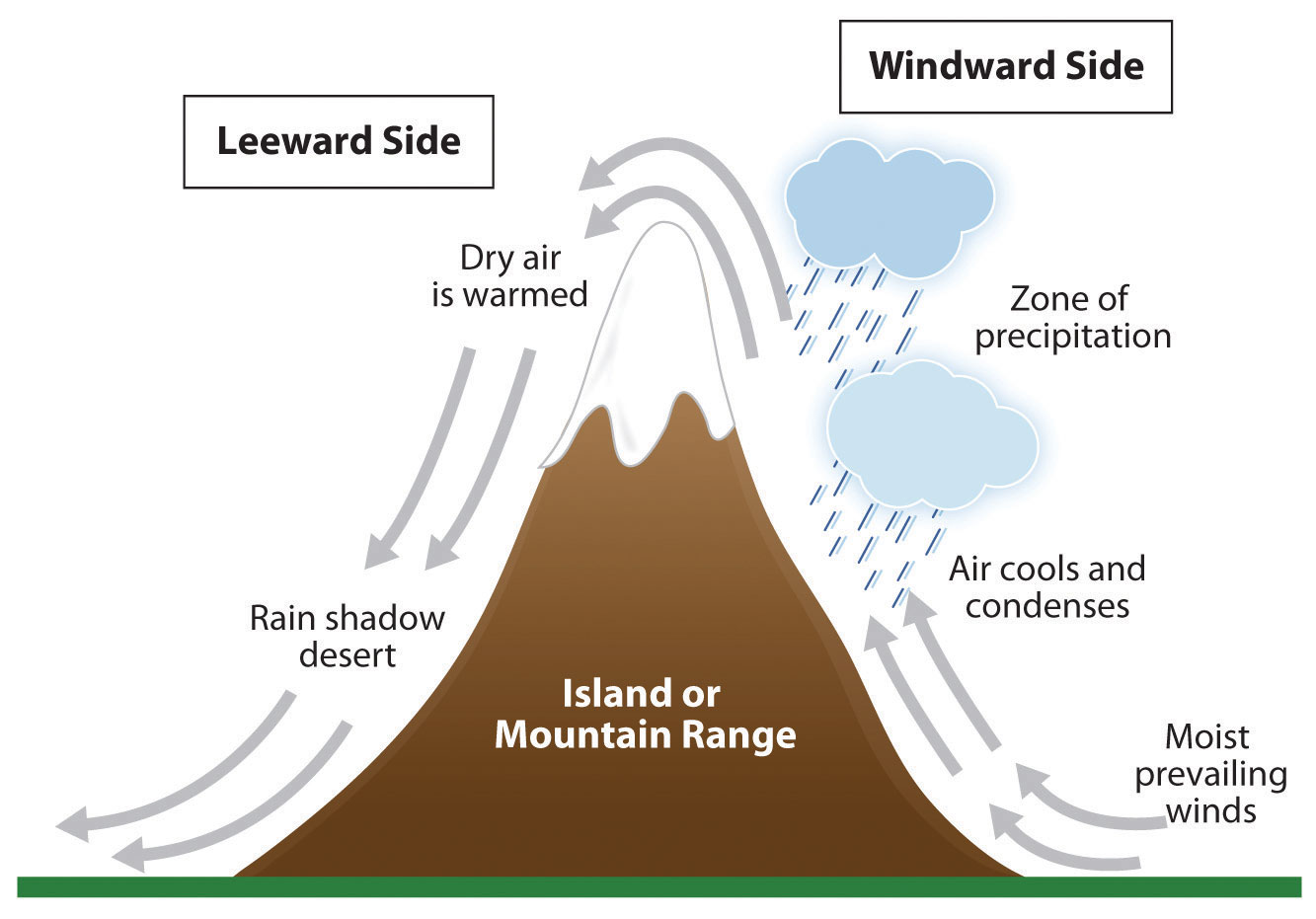

The Rain Shadow Effect

The rain shadow effect demonstrates how physical geography directly influences human settlement patterns. When moisture-laden air masses rise over a mountain range, they cool and release precipitation on the windward side. By the time the air descends on the opposite (leeward) side, it has lost most of its moisture, creating arid conditions.

This phenomenon shapes entire civilizations:

- The Himalayas create the Gobi Desert in western China while southern India receives abundant monsoon rains

- The Sierra Nevada creates Death Valley, one of the driest places in North America

- The Andes create the Atacama Desert, the driest non-polar desert on Earth

- Hawaii's Kauai receives nearly 40 feet of rain annually on one side while having near-desert conditions on the other

🔠Geographic Inquiry

Consider the "Rain Shadow Effect" shown in Figure 1.2. If a region's prevailing winds change due to global climate shifts, how might that transform the agricultural potential of the communities living on either side of the mountain? What economic and social disruptions could result?

👥 Human Geography: The Cultural Landscape

Human geography examines how human activities - migration, culture, industry, and politics - interact with the Earth's surface. It bridges the social sciences with spatial analysis to understand the cultural landscape: the visible imprint of human activity on the land.

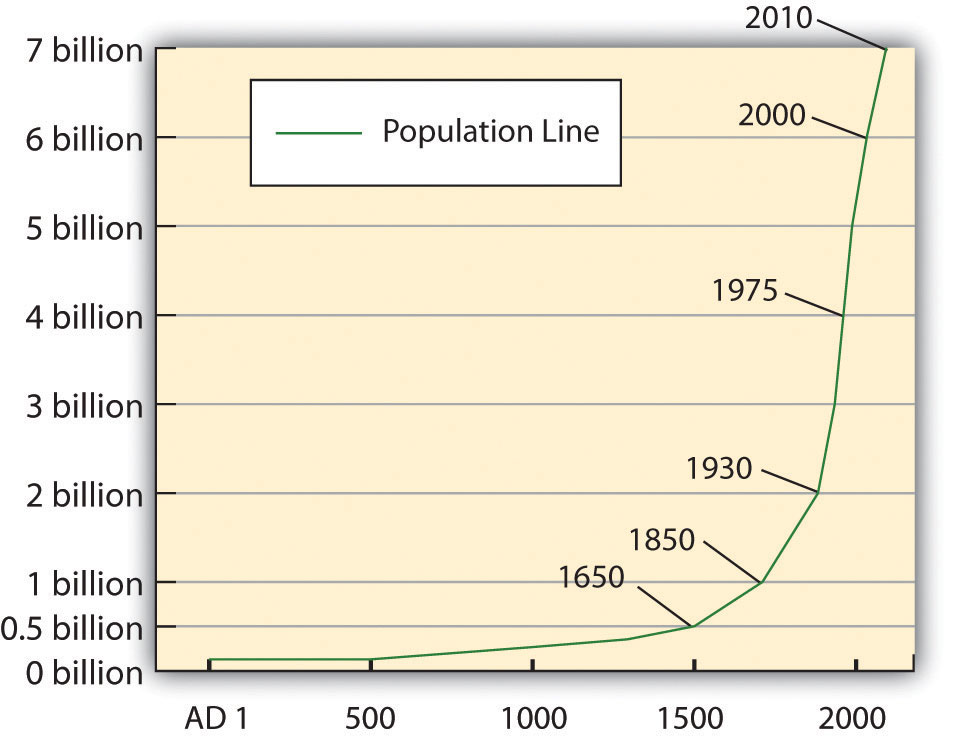

Population Geography and the Demographic Transition

Demography is the study of how human populations change over time and space. For most of human history, world population grew slowly—only about 500 million people lived on Earth in 1650. The Industrial Revolution changed everything.

The demographic transition describes how societies move through predictable stages:

- Stage 1 (Pre-Industrial): High birth rates and high death rates, resulting in slow population growth

- Stage 2 (Early Industrial): Death rates fall due to better nutrition and sanitation, but birth rates remain high, causing rapid population growth

- Stage 3 (Late Industrial): Birth rates begin to fall as children become economic liabilities and women gain education and employment

- Stage 4 (Post-Industrial): Low birth and death rates lead to population stability or decline

📊 By the Numbers: World Population

- Year 1: ~300 million people

- 1650: ~500 million people

- 1900: 1.6 billion people

- 2000: 6 billion people

- 2024: 8+ billion people

- 2100 (projected): 10-11 billion before stabilization

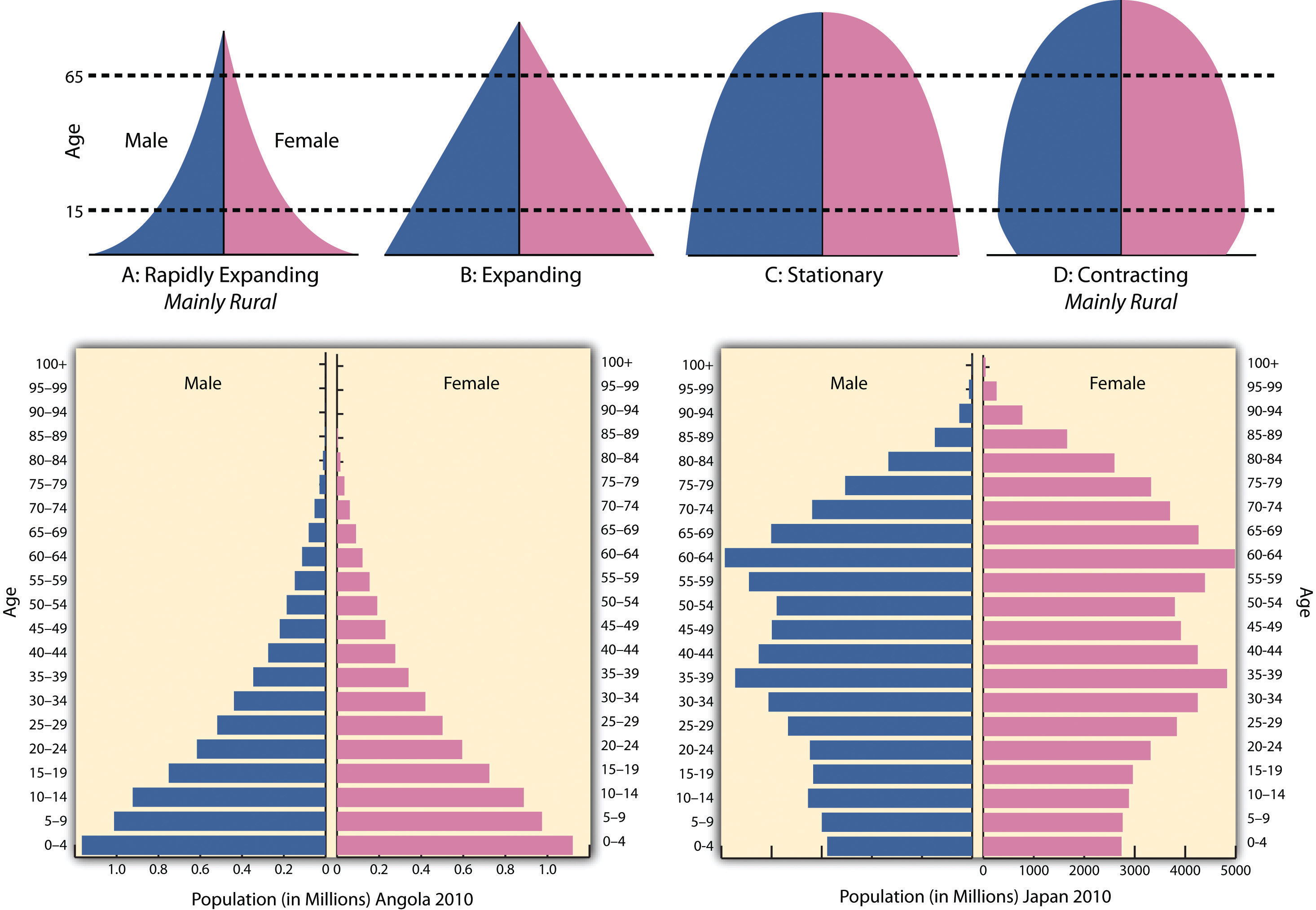

Understanding Population Pyramids

A population pyramid graphically represents a country's demographic structure by age and sex. The shape tells us about past, present, and future trends:

- Wide base, narrow top: Rapidly growing population (common in Sub-Saharan Africa)

- Rectangular shape: Stationary population with stable birth and death rates (common in Europe)

- Inverted pyramid: Declining population with more elderly than young (emerging in Japan, Italy)

Culture, Language, and Religion

Culture encompasses everything people learn after birth—language, religion, customs, and traditions. These cultural elements create distinct patterns across the geographic landscape.

Language is fundamental to cultural identity. Linguists estimate there are over 6,900 living languages, though many are spoken by small populations and face extinction. The major language families include:

- Indo-European: Includes English, Spanish, Hindi, Russian, and Persian—spoken by nearly half of humanity

- Sino-Tibetan: Includes Mandarin Chinese, the world's most spoken first language

- Afro-Asiatic: Includes Arabic and Hebrew

- Niger-Congo: Africa's largest language family, including Swahili and Yoruba

Religion shapes cultural landscapes through architecture, land use, and social practices. Major world religions include Christianity (2.4 billion adherents), Islam (1.9 billion), Hinduism (1.2 billion), and Buddhism (500 million).

Globalization and Glocalization

Key themes in human geography include Globalization - the increasing interconnectedness of people and places - and Glocalization - the way global forces are adapted to fit local cultural contexts.

🌐 Examples of Glocalization

- McDonald's offering McAloo Tikki burgers in India (vegetarian) and Teriyaki burgers in Japan

- IKEA designing smaller furniture for Asian apartments

- K-pop blending Western musical styles with Korean cultural elements

- Hollywood films being remade for Bollywood audiences

🛠️ Geographic Tools and Technologies

Modern geographers have an extraordinary toolkit for studying the Earth. These technologies allow us to analyze patterns, predict changes, and understand spatial relationships in ways that early geographers could never have imagined.

Cartography: The Art and Science of Map Making

Cartography has evolved from hand-drawn maps to sophisticated digital representations. Maps remain the most powerful way to communicate spatial information, but all maps involve choices about what to include, exclude, and emphasize.

ðŸ—ºï¸ Map Projections Matter

Every flat map distorts our spherical Earth. The famous Mercator projection (1569) preserves shapes for navigation but dramatically inflates the size of polar regions—making Greenland appear as large as Africa, when in reality Africa is 14 times larger! Different projections serve different purposes, and no map is perfectly "accurate."

Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

GIS is computer software that allows geographers to layer, analyze, and visualize spatial data. By combining multiple data layers—population density, elevation, roads, land use—GIS reveals patterns invisible on any single map. Applications include:

- Urban Planning: Identifying optimal locations for new schools, hospitals, or transit lines

- Environmental Management: Tracking deforestation, predicting flood zones, mapping wildlife habitats

- Business Intelligence: Determining store locations based on demographics and competitor analysis

- Disaster Response: Coordinating evacuation routes and resource deployment

Global Positioning System (GPS)

The GPS uses a network of satellites to pinpoint exact locations on Earth's surface. Originally developed for military navigation, GPS now powers everything from smartphone maps to precision agriculture. A GPS receiver calculates position by measuring signals from at least four satellites, achieving accuracy within a few meters.

View the GPS Workshop →Remote Sensing

Remote sensing acquires information about Earth from a distance, typically through aerial photography or satellite imagery. This technology allows geographers to:

- Monitor crop health and predict harvests

- Track urban sprawl and land use changes over decades

- Measure glacier retreat and sea ice extent

- Detect illegal deforestation in real-time

- Assess damage after natural disasters

💡 Try It Yourself: Google Earth

Google Earth is a free tool that demonstrates remote sensing principles. Use the "historical imagery" feature to see how your neighborhood has changed over decades. Examine satellite views of the Amazon rainforest, melting glaciers, or the growth of cities like Dubai or Shanghai.

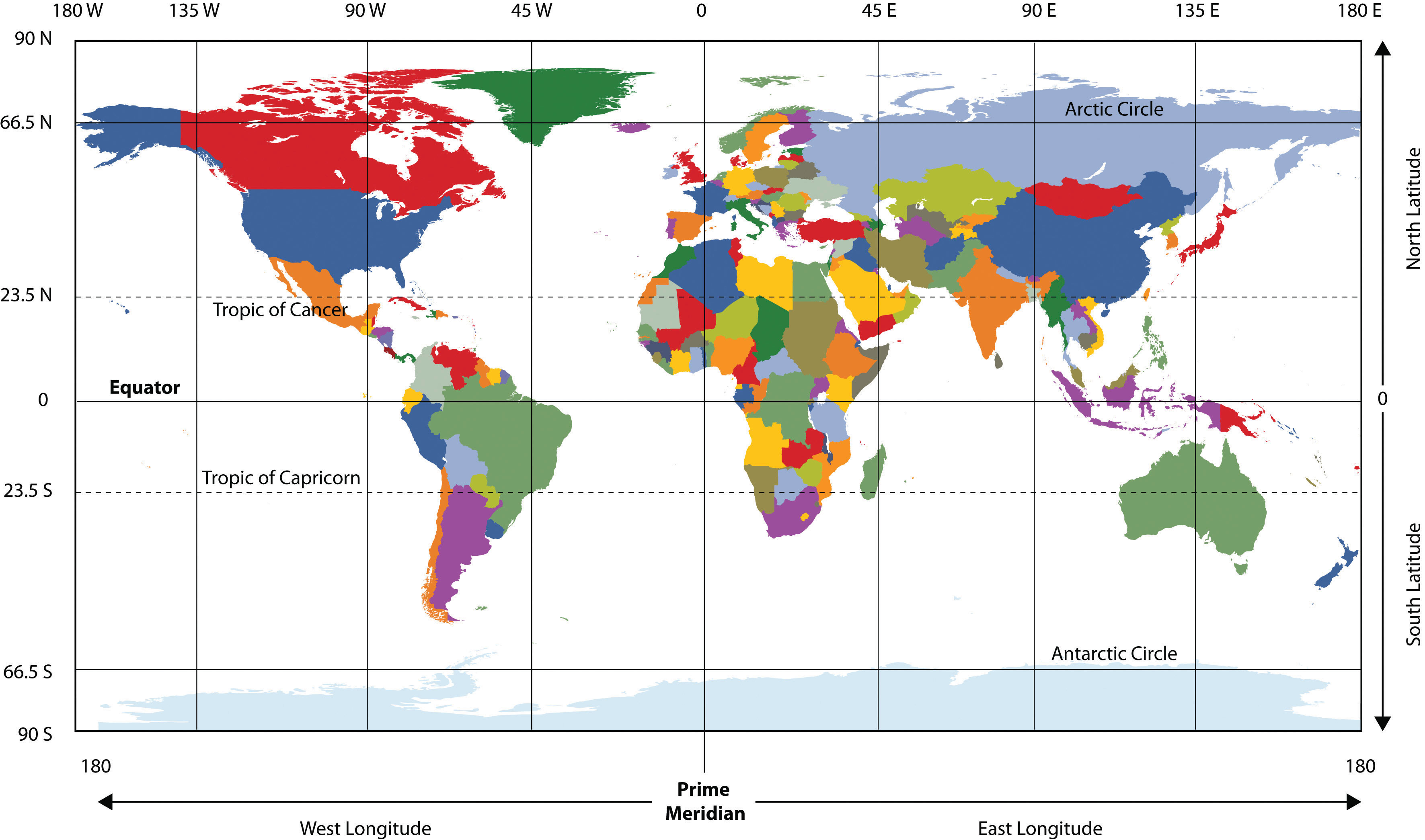

Launch Google Earth 🌍🌐 The Earth's Grid System: Latitude and Longitude

To locate any point on Earth precisely, geographers use a grid system called the graticule. This system divides the globe into 360 degrees using imaginary lines.

Lines of Latitude (Parallels)

Lines of latitude run east-west and measure distance north or south of the Equator (0°). Key parallels include:

- Tropic of Cancer (23.5°N): The northernmost point where the sun is directly overhead (June solstice)

- Tropic of Capricorn (23.5°S): The southernmost point where the sun is directly overhead (December solstice)

- Arctic Circle (66.5°N): Marks the boundary of the polar day (24-hour sunlight in summer)

- Antarctic Circle (66.5°S): Southern equivalent of the Arctic Circle

Lines of Longitude (Meridians)

Lines of longitude run north-south and measure distance east or west of the Prime Meridian (0°), which passes through Greenwich, England. The International Date Line (180°) marks where each calendar day begins.

Time Zones

Because Earth rotates 360° in 24 hours, it moves 15° per hour. Time zones are roughly 15° wide, though political boundaries often modify exact boundaries. When it's noon in London (0°), it's:

- 7:00 AM in New York (75°W)

- 4:00 AM in Los Angeles (120°W)

- 9:00 PM in Tokyo (135°E)

🔠Geographic Inquiry

Why might a country like China, which spans five "natural" time zones, choose to operate on a single time zone? What are the advantages and disadvantages for people living on the far western edge versus the eastern coast?

What Makes "Europe" a Region?

Europe is one of the most complex regions to define. Physically, it isn't a separate continent at all, but rather a large peninsula of the Eurasian landmass. So why do we study it as a distinct region?

Physical Boundaries: Traditionally, the Ural Mountains and the Ural River mark the eastern edge. However, these are low mountains that have rarely stopped the flow of people or ideas.

Cultural & Political Boundaries: Geography often defines Europe by its shared history of the Renaissance, the Industrial Revolution, and democratic traditions. Today, the European Union (EU) represents a "functional region" where nations share a currency and open borders, yet many "European" countries like Switzerland or Norway remain outside the EU's formal political structure.

Questions to Consider:

- Is Europe defined more by its physical landscape or its cultural identity?

- How does the "perceptual region" of Europe change if you are standing in London versus standing in Istanbul?

✅ Knowledge Check

Loading quiz questions...

Drawing the Map: Where Should the Border Go?

You are a geographer advising a newly independent nation that has just separated from a larger country. You must recommend where to draw the new international border. The territory in question contains a mix of ethnic groups, valuable natural resources (a river and oil fields), and a major city that both sides claim. There is no "perfect" answer — only trade-offs.

🗺️ Role A: Physical Geographer

You argue that borders should follow natural features — rivers, mountain ranges, watersheds. These create defensible, logical boundaries. You recommend the river as the border, even though it splits an ethnic community in two.

👥 Role B: Cultural Geographer

You argue that borders should follow ethnic and linguistic communities — keeping people who share culture and language together. You recommend a border that keeps the ethnic community unified, even though it cuts across the river and leaves the oil fields on the "wrong" side.

💰 Role C: Economic Geographer

You argue that borders should maximize economic viability. Each new nation needs access to resources, ports, and trade routes. You recommend a border that gives each side roughly equal economic assets, even if it creates an awkward shape.

⚖️ Role D: Political Geographer

You argue that the most important factor is stability — a border that both sides can accept and defend. You recommend a compromise border based on the current line of control, even if it is geographically illogical, because changing it would require war.

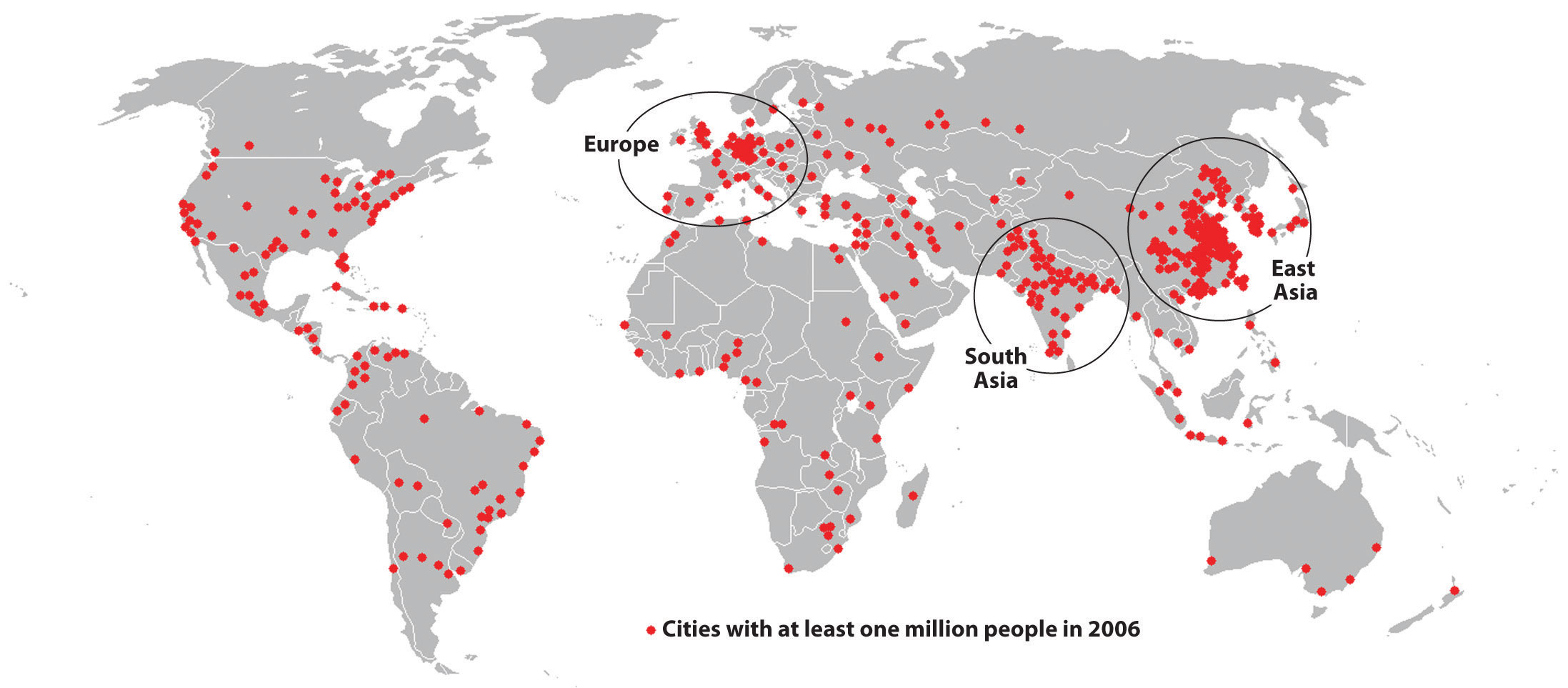

📊 Data Exploration: Where Do People Live?

One of geography's most fundamental questions is: why do people live where they do? The chart below shows the percentage of world population living in each major world region. Notice how unevenly distributed humanity is — and consider what physical and human geographic factors explain these patterns.

Geographic Inquiry: Asia contains nearly 60% of the world's population but only 30% of its land area. What physical geographic factors (climate, rivers, fertile soil) and human geographic factors (agriculture, trade routes, history) explain this concentration? How does this distribution connect to the five themes of geography?

💬 Discussion & Reflection Prompts

Reflect on Your Learning

- Personal Connection: Which geographic concept connects most to your own place or community? How does geographic thinking help you understand it differently?

- Scale Analysis: Choose a problem you care about (climate, migration, poverty). How would you analyze it at local, regional, and global scales? What patterns emerge?

- Map Making: If you created a map of something important to you, what would you show? What would you leave out? What does that reveal about representation?

Discuss With Your Peers

- What surprised you most about how geographers think about the world?

- How might a geographer approach a problem differently than a historian or economist?

- Can you think of an example where geographic understanding resolved a real-world challenge?

📊 Curriculum Standards Alignment

This chapter aligns with the following National and State geography standards.